10 April 2020

The pandemic must be represented by a graph so that it can be managed figuratively, if not literally. The phrase “flatten the curve” and the inverted U-shaped plot now rule the fate of entire nations. With the rather sordid rates of testing for the novel coronavirus in India, the figurative register can at times seem more necessary to control than the actual disease incidences. The Indian government’s repeated denial of “community transmission” in the country despite its own research agency’s (the Indian Council of Medical Research) findings seems to confirm this structural fascination with thin lines rising at a small angle. The pandemic, of course, is quite capable of representing itself by manifesting through its symptoms. But maybe it still has some way to go before its less fortunate victims – whose conditions worsen or who are socially disadvantaged enough to fall outside the calculus of official numbers – swell in volume to overwhelm the outlines of the state’s vision. One also certainly hopes for that to not happen.

SARS-CoV-2 has had a more iconic entry into the realm of representation compared to the minimalist linear depiction of its effects on large population bodies. We have now become very familiar with the spherical orb with a crown of club-shaped spikes that has come to mark the regent amongst the horrors confronting human life – so much so that now there is a sweet in my city modelled after the virus (as shown in the image below, photo 1)! The background to this is that the state government has recently allowed sweet shops to operate for four hours every day in a partial relaxation of the lockdown. There is some catering to the proverbial sweet tooth of the Bengali middle-class here, but also perhaps some dire recognition of the sheer uncertainty amongst local businesses and employment that now has begun to worry provincial political leaders. Alongside reviving their businesses, the shops in question also seem to have risen up to the occasion to deliver some well-timed, let’s just call it, corona-kitsch. I lack the training or the instruments to comment on the likeness between this representation and the reality. But the liberal payload of edible pink and red colour contained in the milk-candy version of the current bane of human existence tells me that the makers were perhaps trying to add some flesh and blood to our microbial imaginary. They seem to have been successful in an odd way. My playschool-going nephew was a bit disconcerted at the sight of the sweet on the evening news. It has since been slightly easier to flesh out the threat of the disease to him. Sweets, it turns out, are not only good to eat, but also great to think with.

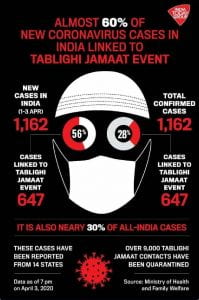

Not all ways of familiarising the disease are as benign. At present, the primary mode of representing the threat of COVID-19 in India is through blatant Islamophobia, the communalism-kitsch that has become more of a staple in the country since at least the election of Narendra Modi as Prime Minister first in 2014. Muslim vendors, workers, and neighbours are being boycotted, brutally beaten up in some instances, and otherwise vehemently blamed for the spread of the disease in the country. The all too usual adversary of the majoritarian Hindu has to now also bear the burden of becoming the symbolic vehicle of the potential of the pandemic. Coronavirus, it is being alleged, is apparently riding a wave of corona-jihad. This representation has been inspired by the finding that a religious gathering attended by international delegates, organised by the group Tablighi Jamaat in New Delhi in early March has led to several cases of transmission amongst its constituents, now spread across the country. The finding has been accompanied by a deluge of politically-motivated fake news about these men not cooperating with health and police officials and even spitting on them in a deliberate effort to spread the virus. What is however being conveniently buried in the news cycle even by relatively less-biased TV channels (for a graphic from one of them, see photo 2) is that the Tablighi Jamaat gathering was the only big group that was screened intensively by the government by conducting sample tests and then eventually by tracing down all of the attendees. Similar sample testing was not done for several other big religious and other kinds of gatherings in the country, some of which continued to assemble even during the lockdown. The Tablighi Jamaat incident could then have exemplified the virtues of testing more; instead, it has domesticated the pandemic by casting it in the mould of a familiar “enemy.” Meanwhile, the state has managed to slip further away from the claims made on its responsibilities. In the foreground remain apparently innocuous-looking graphs and equally dangerous-looking skull-caps, and some saccharine assurance that the curve is not too steep after all.

<< Previous Next >>

Ritam Sengupta is finishing his Ph.D. in Social Sciences at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta. He is based out of Kolkata, India. His doctoral project deals with the history of electrification in colonial and postcolonial India over the twentieth century that attempts to foreground transitions in energy regimes as one key to thinking the political and economic transformations in the region in this period. One part of the project, developed while undertaking a fellowship at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, concerns the history of the arrival of electricity to the northern Indian countryside as the energetic basis of irrigation from underground resources.

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science(Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)