There is no newspaper or television program these days that does not talk about toilet paper. Or, rather, that does not talk about the inexplicable anxiety felt by those trying to secure just one roll, or expressed by those stockpiling it by the dozens. Let us take advantage of the situation these days to trace some of the history of paper; and along the way challenge the mania some Americans north of the Rio Grande have for conflating the registration of a patent for a new technology with the actual invention of these grand innovations for humanity. One of these histories is the appearance of toilet paper in modern life, commonly attributed to Joseph C. Gayetty, a Pennsylvania-born inventor living in New York, who held the first patent in the United States for a hygienic paper. Gayetty’s medical or therapeutic paper was, in fact, the only toilet paper marketed in the United States between 1857 and 1890. The original product was made from pure Manila hemp, contained aloe as a lubricant, and was marketed as an anti-hemorrhoidal medical product. It melted easily in the water and did not clog drainage pipes, as ordinary paper did. In 1859, Gayetty established a storefront in New York at 41 Ann Street, where he sold 1,000 sheets for one dollar.

“The greatest necessity of the Age,” proclaimed Gayetty in his advertisements aimed at both women and men, for both the toilet and the lavatory. Many people—continued the businessman—“wooed their own destruction, physical and mental, by neglecting to pay attention to ordinary matters,” that is, the poisons that entered the body by “applying that ink to the tenderest past of the body corporate” in the name of hygiene. We must not forget: this paper had to establish itself—or rather, compete—with the free alternatives of the time. Because, it goes without saying, that even before Mr. Gayetty’s patent, people had been wiping their bottoms and blowing their noses with more than just their hands. After all, as we have been often told, human beings are defined by their ability to make tools; and to transform nature into culture—even at the moment of expulsion through the digestive tract or by sneezing.

Without going too far into the subject, in the urban and rural world of the nineteenth century, the pages of almanacs and pulp writers, yesterday’s newspapers, the pages of outdated catalogues, even tree leaves and corn husks were used for wiping. Gayetty pointed out in his advertisements that the words in these books and newspapers carried poison. Enameled cards contained a quantum of arsenic and other potentially deleterious chemicals. Even higher-quality paper for printing or writing was impregnated with chloride of lime, oil of vitriol, potash, white clay, lime, oxalic acid, soda ash, or ultramine. White paper, especially, concentrated the sum of all of these chemicals. Colored paper embodied portions of prussiate of potash, bichromate of potash, muriatic acid, Prussian blue, aqua-fortis (nitric acid), copperas and many other elements equally harmful to the sphincters and mucous membranes of their users. Touching them or trying them was therefore nothing more than playing with a harmful material that transmitted death, an action similar to ingesting ink or rubbing lamp black into eyes, gums, noses and private parts. Faced with the costs associated with this risk, would it not be cheaper to cleanse oneself, to dry oneself or to evacuate the discomfort, smell and itching of headcolds, urine and feces by resorting to a paper treated with aloe and marked with the name of the inventor, which, as if that were not enough, also cured the most painful ailments?

Gayetty was criticized as a charlatan by medical magazines and associations: “Quackery in a new aspect. Empiricism has changed tactics”—so alerted the Medical and Surgical Reporter from Philadelphia, which stressed that the gall of these health dealers was such that they now attacked the public in the rear, catching them with their breeches down and leading them to the need to buy their “medicated toilet paper.” Furthermore, the New Orleans Medical News and Hospital Gazette opined: “It must be valuable, and we suggest that he not only place his autograph on each sheet of his invaluable paper to prevent counterfeit, but that he furnish his millions of patrons with his photograph, in like manner. More we suggest that the photograph be taken with a bland smile on the face. We are, really anxious to see the face of the man who is going to eclipse even homoeopathy in the inestimable benefits he this rubs into mankind; and then, again, it would be such a capital idea to be thus cheering up the sufferer by smiling on the very seat of his troubles.”

But in no way did the suffering and frightened human population, or at least those resident in the United States, went out to the streets to purchase the new product. And even though the users indeed before cleaning up, indeed had to look carefully at every sheet of Gayetty paper (instead of reading the news about to be discarded), this was not so much to verify the presence of the inventor’s signature, but to look for the splinters that could prick them in one impetuous wipe.

This was because Gayetty’s paper, which was indeed beautifully pearly white and pure as snow, was made from Manila hemp: that is, a vegetable fiber composed of cellulose, lignin and pectin obtained from Musa textilis or abaca. This large herbaceous plant used in the textile industry, native to the Philippines and similar to the banana tree but with inedible fruits, was known by Europeans since Magellan’s trip in 1521. In the Philippines, it was grown and used in bulk by the local population for the manufacture of textiles and it quickly became part of the economy of the Catholic Monarchy. By 1897, the Philippines exported almost 100,000 tons of abaca and it was one of the three most important cash crops of the Spanish colony, along with tobacco and sugar. In fact, from 1850 to the end of the nineteenth century—when Spain ceded the islands to the United States—sugar and abaca alternated as the largest export crop from the Philippines. It was used for the manufacture of rope in New England, as well as in Manila paper envelopes and in the making of paper money. Thus, unwittingly or not, Gayetty’s medicated paper was born already associated with the deeper fibers of money, American expansion and global circulation at the time—that is, the ropes required by the New England East Coast whaling ships which, in those years, moved and connected much of the world economy.

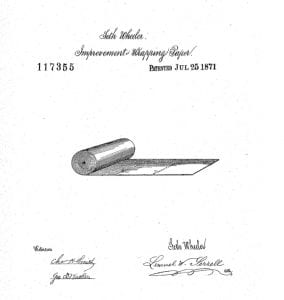

The history of toilet paper, of course, continues and hopefully it will continue to evolve. But it was not until the 1930s that Northern Tissue invented a “splinter-free” toilet paper, which, thanks to a late nineteenth century patent filed by another Albany man, was from the start sold in a rolled form. These are the direct ancestors of the rolls that generate so much ink today. However neither they, nor Gayetty’s paper, probably cured even a single hemorrhoid.

This piece originally appeared in Spanish as Republicado (con un título diferente) de: Irina Podgorny, “Coronavirus ¡Mi reino por un rollo de papel!”Revista Ñ, 21 March 2020, 12. This is an English translation of the original piece as syndicated by Teach311 + COVID-19.

Irina Podgorny is a permanent research fellow at the Argentine National Council of Science (CONICET). She studied Archaeology at the La Plata University, obtaining her Ph.D. in 1994 with a dissertation on the history of archaeology and museums. She has been a research fellow at the MPIWG Dept. III Rheinberger (2009–10), she was also a postdoctoral fellow at Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut Berlin and at MAST (Museu de Astronomia) in Rio de Janeiro. Irina’s current research project deals with historic extinctions and animal remedies. At the MPIWG she is also a member of the Body of Animals Working Group in Dept. III. In addition to her academic research, Irina collaborates with Argentine cultural weeklies and Latin American artists, most recently for a 2018 art exhibition in Lima, Perú. She has been a member of the Editorial Board of Science in Context since 2003 and History of Humanities since 2017, and has recently been elected president of The History of Earth Sciences Society. Her current work focuses on the history of paleontology, museums of natural history, and archaeological ruins.

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science(Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)