‘Education is thus constantly remade in the praxis.’ – Paulo Freire

In the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, teaching has become inextricably entangled with the contemporary moment as mainstream educators have reckoned with the upheaval of the pandemic, of massive logistical change, and of teaching amid this moment of acute concurrent disasters. As a poet, publisher, and current PhD student I’m still figuring out what kind of academic I want to be and what I want from my relationship to the institution, specifically I’m interested in how pedagogy overlaps with phenomenologies of care, kinship, and community. I’ve started looking to the lecturers around me at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), in the School of Humanities, who’ve chosen to address the ongoing circumstances within the seminar setting. In doing so, they’ve created hospitable spaces through which to figure out the contexts we’re currently immersed in, and I’m in interested in this, in the ways we organise energy within the institutional space and how this aligns us in dialogue with our being in the world. In seeking to better engage students with the discourse bound to the present, how do we practice pedagogy without reinforcing the violences of corporate consumerism – how can lecturers discuss the pandemic while practicing the transmission of knowledge in solidarity and as an act of care?

I asked Assistant Professor Olav Vassend about the HY3010: Philosophy of Science course, which centred COVID-19 within discussions on public health efforts, state responsibility, and risk.

The starting point was an article by Jonathan Fuller in the Boston Review that contrasted the response to COVID-19 recommended by clinical epidemiologists, on the one hand, and by public health epidemiologists on the other. Clinical epidemiologists put a premium on evidence that comes from large observational or—ideally—randomized controlled trials and have tended to be highly sceptical of drastic responses to COVID-19, given the lack of such evidence. Public health epidemiologists, on the other hand, are comfortable recommending public health interventions on the basis of a much wider range of evidence, including computer simulations, and have tended to recommend much more drastic interventions, such as lockdowns. The main question in the class was what kind of evidence is required in order for authorities to make rational public health recommendations and/or mandates (such as, for example, mask-wearing or lockdowns). We also discussed rational decision-making and decision theory more generally as this topic had already come up earlier in the semester, and we read responses to Fuller’s article by John Ioannidis (a prominent clinical epidemiologist) and Marc Lipsitch (a prominent public health epidemiologist), among others.

Has teaching been different in comparison to other years, both for you and the students on the course?

Because the class met in person, teaching philosophy of science this semester wasn’t all that different from usual, except that everyone had to wear a mask. I guess one major consequence of the fact that everyone in the class wore a mask was that I was never able to learn all the students’ names, which I usually do. As for how the students reacted to the unit on COVID-19—most of them seemed to treat it like any other topic. Speaking for myself, my life after the pandemic began has been very different from how my life was before the pandemic, but my impression was that life is more or less back to the way it used to be for many of the students.

I’m curious how the class responded to discussion on how state and health authorities make public mandates? The amount of information and misinformation that has emerged around COVID-19 has seemed prolific, how did you decide which materials and epidemiologist to operate conversations around?

As for how I chose reading material—the required reading was an exchange in the Boston Review between a philosopher of science and two epidemiologists. The philosopher of science specializes in philosophy of medicine, and the epidemiologists are both very famous and have had a prominent role in issuing (at times conflicting) recommendations in the media and to governments, so this exchange seemed like a good starting-point for an in-class discussion. I also included (as an optional reading) an article on how the pandemic has become politicized. However, the politicization of COVID-19 seems to have been more of an issue in the US, in particular, and in Europe to a lesser extent. It doesn’t seem to have been as much of an issue in Singapore, and the topic did not come up during class discussion.

Earlier in the semester, we covered decision theory (the theory that deals with how to make rational decisions on the basis of evidence), so I tried to make the students connect the discussion between the participants in the Boston Review debate to our discussion of more general decision theoretic principles, for example with regards to how utility considerations should guide policy recommendations. For example, mandatory mask wearing has a potentially large benefit and comparatively few drawbacks, so less scientific evidence might be required to make it rational to mandate mask-wearing than, for example, to justify more onerous restrictions, such as a complete lockdown. In this context, I asked the students to come up with their own decision theoretically based analyses, which we could then critique. Of course, neither I nor the students are public health experts, so the analyses we came up with were highly simplistic, but I think it was still an instructive exercise. I believe the decision theoretic perspective helped students make sense of various governments’ actions at different stages during the pandemic. At least that was the goal. It was not my goal (with this unit) to alter the perception of science that students have.

I’m not sure if I will keep the unit on COVID-19 when I teach the class again in the future. I guess I will probably keep it if I offer the course in the relatively near future, but at some point, I imagine the content will no longer be interesting to students (when the pandemic is behind us, which will hopefully not be in too long!).

By approaching the pandemic with a necessary uncertainty, lecturers in the school of humanities have discussed COVID-19 in collaboration with students, refusing the fixity of student-teacher binaries. I think this exchange is fundamental in rejecting the inequitable hierarchies that often appear within the university. In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paolo Freire argues against the banking concept of education which posits the teacher as containing all the jewels and the students as trying to get rich. He challenges the commodification of knowledge within the institution as he asserts, ‘education must begin with the solution of the teacher-student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of contradiction so that both are simultaneously teachers and students’ (Freire, 2017, p. 45). In this time, it feels as though the authority over knowledge has eroded a little in regards to the pandemic, we’re all uncertain and relearning how to be. To Freire, the strict distinction between teacher and student ‘maintains and even stimulates the contradiction through […] attitudes and practices, which mirror oppressive society as a whole’ (Ibid.); perhaps in rethinking pedagogical praxis, the pandemic has carved out a space through which to re-think the classroom, authority, the communication of knowledge, and solidarity. This in itself could be considered a radical act in Singapore – a transactionally oriented society in which protest is illegal. To me, learning how to communicate and listen within the university setting is inextricably linked to forms of activism through pedagogy as an act of care.

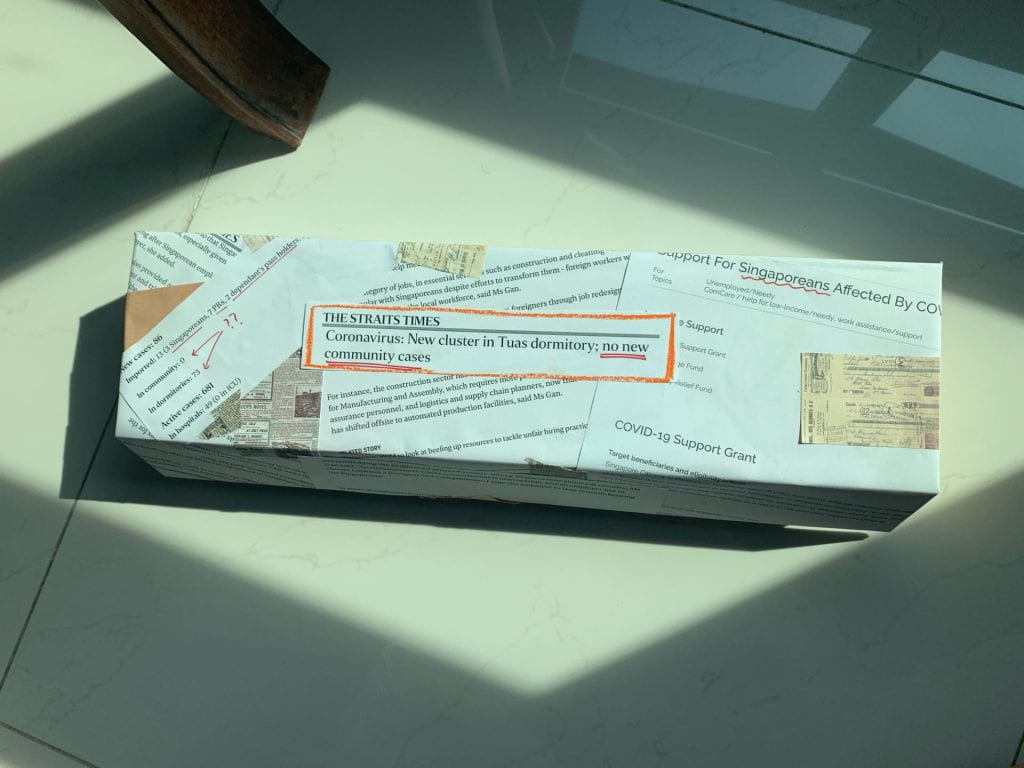

I asked Dr Melvin Chen about this. At the start of the lockdown in Singapore, he shared links to virtual museum tours, films, performances by Cirque du Soleil, operas, as well as articles identifying the psychological risk of too much media exposure, and a to-do list to manage social isolation, courtesy of Mihai Șora, a 103-year-old philosopher. These were shared with his SP0002: Ethics and AI6101: Introduction to AI & AI Ethics classes as an aid to help them through lockdown, while encouraging them to consider various ways of thinking about and coping with COVID-19. Following the spike in cases at the dormitories of migrant workers, Dr Melvin also shared resources with students who were interested in supporting the Migrant Support Coalition or Migrants We Care campaigns, although he assured them that they were entirely within their means to refrain from doing so.

I’d also really like to ask if the content of the work that students have submitted on the Ethics, Introduction to AI & AI Ethics, or Philosophy of AI courses has been affected by COVID-19? In some of the modules I audited, some of the work focussed a lot more on loneliness and parsing out different state responses to the pandemic, and I was wondering if this was the case in your classes too?

Several students became markedly more interested in the applied rather than the theoretical aspects of my courses. I was able to infer this from the kinds of questions being posed. The theoretical aspect of SP0068: Philosophy of AI concerns the various approaches to AI research (classical, neural network-based, Turing test-related, etc). The applied aspect concerns the application of these various approaches to specific real-world problems. The theoretical aspect of SP0002: Ethics is typically located in metaethics and normative theory, whereas the applied aspect is located in applied ethics. Students became more interested in how AI might be applied to the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19-related applied ethical issues. This gave me an incentive to develop the applied aspects of Philosophy of AI and Ethics and offer COVID-19 as a context for discussion and debate. This move helped to drag philosophy as a discipline out of its traditional ivory tower and encouraged students to draw connections between what they might learn in class and a global and topical concern.

Besides Mihai Șora, were there other philosophers that you found resonating with the current moment? I found myself rereading Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (Foucault, 1975) during that time alongside Donna Harraway’s Staying With The Trouble (Haraway, 2016) as ways of thinking through hope, crisis, and survival.

A number of philosophers have responded to the moment with COVID-19-related research. They are typically applied ethicists. Lynette Reid (one of our guests on the NTU Medical Humanities seminar series on epidemics), Govind Persad, and Ezekiel Emanuel have been quite active on this front. Thinking about the just allocation of resources (basic necessities and masks in the early days of hoarding, triage and the distribution of ventilators when countries began encountering critical shortages in ventilators, and vaccines in 2021) has made me consider John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice (Rawls, 1971) as worth a re-read.

As all the uncertainties have been made both hypervisible and communal, I’ve been asking what I’m supposed to as a lecturer, not at the front of the room but visibly at the centre of attention, and I think perhaps one answer is to redirect that attention back outwards – to disappear into the discussion and facilitate the space with those around me. Freire acknowledges this necessity of collaborative knowledge formation, stating; ‘authentic thinking, thinking that is concerned about reality, does not take place in ivory tower isolation, but only in communication. If it is true that thought has meaning only when generated by action upon the world, the subordination of students to teachers becomes impossible’ (Freire, 2017, p. 50). He continues, widening the scale of inclusivity as he proposes ‘one does not liberate people by alienating them’ (p. 52), he calls for teachers to ‘abandon the educational goal of deposit-making and replace it with the posing of the problems of human beings in their relations with the world’ (Ibid.). In our immediate relation with COVID-19, lecturers have encountered the difficulty of facilitating an educational practice which engages in nuanced, kind, and intellectually rigorous discussions around a crisis that is still ongoing. At NTU, this has been especially prevalent within medical settings and within the interdisciplinary medical humanities courses which combine scholarship on heath, sickness, and literature.

Assistant Professor Michael Stanley-Baker works within NTU’s History department as well as at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine (LKC), teaching within both disparate spheres.

In Medical Humanities at LKC, we rewrote the entire lesson on contagion, which synchs with the “Infection” block in the Medical School curriculum. In previous years we focused on AIDS. This time, we considered political, racial, and anthropological perspectives on COVID-19, introducing Foucault’s notion of the biopolitical, and Mary Douglas’ notion of pollution as matter out of place, discussing them in the context of Singapore. We also prepared video interviews of physicians who served in the migrant laborer camps and on the ICU ward at the National Centre for Infectious Diseases, who described their experiences. One of them wrote an essay about her time on ICU, which I am also publishing in a special edition of Asian Medicine. Students then designed ethnically-sensitive public health posters in different languages. In HH3002: Science and Technology in East Asia, students attended a live webinar I hosted with leading scholars and practitioners of Chinese and Tibetan medicine concerning how these traditions have responded to the outbreak within China and abroad. We read a number of articles about COVID-19 and SARS in East Asia, the Singapore Bio-surveillance technology TraceTogether, and toilet paper panic buying for the following week’s discussion.

COVID-19 also appeared in Stanley-Baker’s HH2015: Biopolitics and East Asian History class in relation to the complex and entangled history of eugenics which engaged with the devastating rhetoric which framed the most susceptible groups as “the elderly and those with underlying health conditions” in Anglo-American contexts.

Investigating the representation of outbreaks within literary and cultural material could also be seen within the amended HL4036: Epidemic Narratives course run by Associate Professor Graham Matthews. The course aimed to explore the myths, facts, and metaphors that shape perceptions of epidemics.

We discussed the 1957-8 H2N2 flu pandemic which was first detected in Singapore, although it originated in China. The week on SARS focused on Singapore. We looked Ireland and China for the week on AIDS. The films Outbreak (Outbreak, 1995) and Contagion (Contagion, 2011) are primarily set in the US. The Plague (Camus, 1991) is set in the French Algerian city of Oran.

I’d really like to ask about the student projects, while some did respond specifically to the pandemic, were there other areas that the pandemic foregrounded more than others – such as domestic violence or structural inequality?

Two excellent student projects about epidemic narratives include a boardgame that models the experience of an epidemiologist during the pandemic, and a diorama about social distancing.

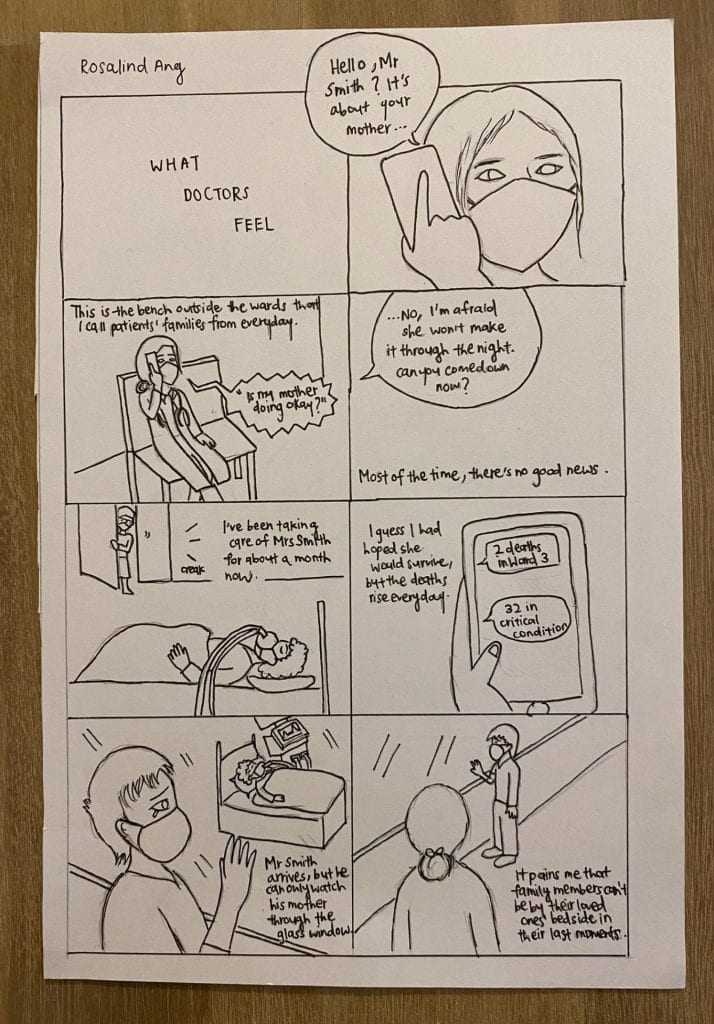

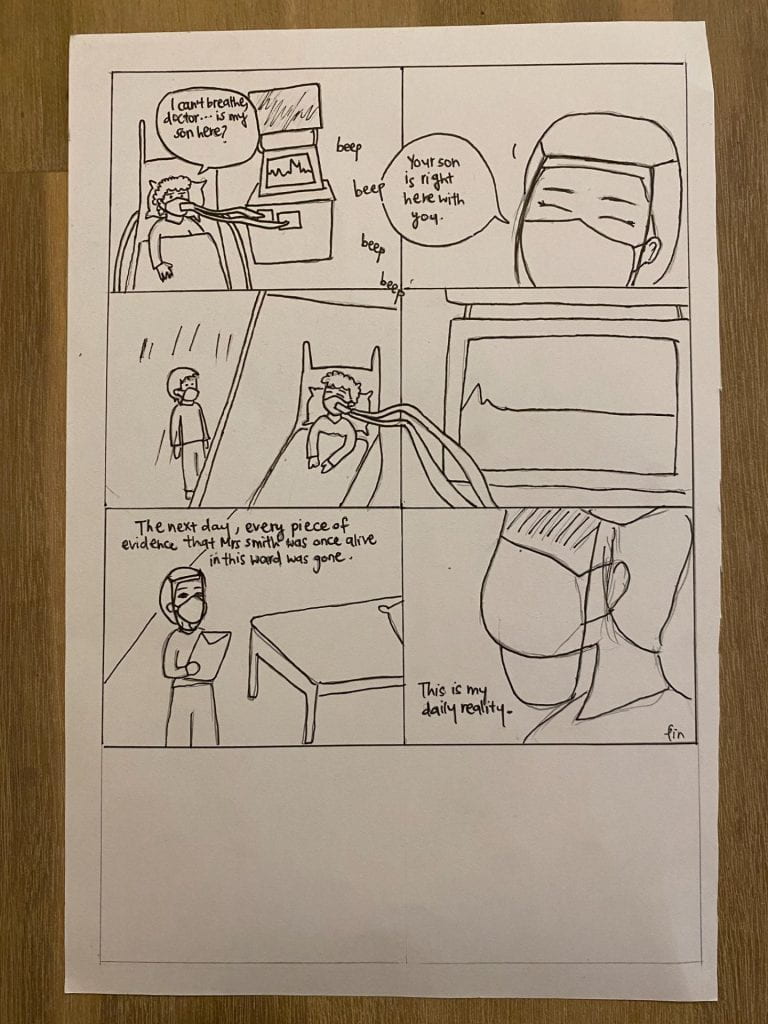

There are also numerous compelling graphic narratives about the pandemic.

Perhaps there’s a hospitality in being able to think through reality at a safe distance – in being able to share a space metaphorically and actually, the institution offers the opportunity to share intellectually rigorous spaces of living. In the last year, I’ve audited enough modules to make up an extra MA, and while most of them have been undergraduate classes consisting of texts I’ve read before it really doesn’t matter to me. It felt important to figure out what it means to be a student in Singapore, in a socio-cultural context so far away from the one I was accustomed to. I learnt just as much from the class as the person facilitating discussion from the front of the room. By moving away from the hierarchal binary of student and teacher, Freire imagines an alternative in which ‘a new term emerges: teacher-student with students-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow’ (Freire, 2017, p. 53). This week, I found out that I’m going to be allowed to teach creative writing in the next academic year – the abstract potentiality of being a lecturer has suddenly become a concrete immanence, I want to be responsive to and responsible for creating a space in which, ‘no one teaches another, nor is anyone self-taught. People teach each other, mediated by the world’ (Ibid.). This practice feels like essential preparation for the people I will meet in 7 months’ time; I’m still learning how to make myself visible in a way that I’m comfortable with while at the same time, keeping myself safe.

Visibility and safety was a central discussion within Dr Geraldine Song’s CY0001: Writing Across The Disciplines for CN Yang Scholars and RE0011: Writing and Reasoning for Renaissance Engineering programmes as the courses included readings from Michel Foucault’s “Panopticism”. Student discussions focused on how the panoptic structure, conceptualised by Jeremy Bentham, could possibly be relevant and applied to the current situation, such as:

- How the panopticon may resemble schools, hospitals, airports, migrant worker dorms etc.

- Surveillance and individual privacy during a plague

I’m curious about how students responded to these ideas within the seminar space?

My course has been running every semester for five years and Foucault’s “Panopticon” has always been one of the readings. Foucault himself mentioned that the Panopticon may resemble schools/education so one of the discussion questions has always been to ask “what other institutions may resemble” the panopticon idea.

The students came with lots of things. We even discussed how our Hive [building] is kind of panoptic, if you were to go nearer the middle, you can see all the tutorial rooms around, and below too. Tan Tock Seng hospital wards also have this panoptic style where the nurses and doctors have their main station in the middle, and all the 5 or 5 bedders are in rooms surrounding them.

Then we have other crazy ideas which the students come up with. They are scholars so they are quite enthusiastic, whatever you throw at them. Anyway, here are other suggestions – sushi restaurant, where the chef sees everything. Nowadays with COVID-19, there may be walls, although see through … quite like Bentham’s original idea. Other ideas – airports, concerts, museums, bookshops. Every year I get something new.

The drone is the single thing that always pops up, as it is the closest thing to the Panopticon – we don’t know we are being watched if at all, and we don’t know who is working on that drone. Surveillance cameras in Little India have come up. A lot of discussion also about self-checking when we are being surveilled. We didn’t chat much about dormitories – more on the already-set-up surveillance system at Little India and parts of Geylang.

In responding to this pandemic moment, these discussions have centred the relationship between human copresence and phenomenologies of community, care, and kinship amid the overlapping structures we all remain enmeshed in. In altering their syllabi, the faculty within the school of humanities at NTU have expanded the curriculum to address the uncertainties and concerns of living that are brought to the seminar, making space for critical thinking which engages with our dynamic and precarious reality. As COVID-19 continues to impact pedagogical practices both in-person and online, engaging in meaningful dialogue remains a priority within the work of educators in the university setting. I don’t think I’ll ever really feel ready to be a lecturer. Perhaps the most radical approach to teaching is to refuse the moniker of teacher altogether, rather, to approach the position of a ‘lecturer’ as an agreement to spend time with the people who want to be in the room together.

Many thanks to Assistant Professor Michael Stanley-Baker, Assistant Professor Olav Vassend, Dr Melvin Chen, Associate Professor Graham Matthews, and Dr Geraldine Song.

References

Camus, A., 1991. The Plague. New York: Vintage.

Contagion. 2011. [Film] Directed by Steven Soderbergh. United States: Participant Media, Imagenation Abu Dhabi, Double Feature Films.

Foucault, M., 1975. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Second Vintage Books Edition ed. New York: Vintage Books.

Freire, P., 2017. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Classics.

Haraway, D., 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

Outbreak. 1995. [Film] Directed by Wolfgang Petersen. United States: Punch Productions, inc..

Rawls, J., 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge: Havard University Press.

Cat Chong is a poet, publisher, and PhD student. They’re a graduate of the Poetic Practice MA at Royal Holloway, and a current PhD student at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore where they’re working at the intersections of disability, gender nonconformity, and lyric intervention. Their interests include illness narratives, ecology, gender, health, contemporary poetics, medical humanities, and crip theory.

***

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)