Scene 1: India. 2020. A four-year-old boy donated his savings of Rs. 971 to the Andhra Pradesh state Chief Minister’s relief fund to fight the novel coronavirus. The Chief Minister shared the heartwarming news on Twitter and assured the child that he will soon gift him the bicycle for which he was saving the money.

Scene 2: United States of America. 1898. A young American girl after viewing images of starving children in India donated her savings for famine relief. “Oh, I can’t be so wicked and selfish as to spend my money on a camera,” the girl remarked. “I hear the cry of those poor little babies all night. This money will almost care for one orphan for a whole year.”

———————————-

The two scenarios above, chronologically apart by over a century, captures an issue that remains current to this day: the connections between humanitarianism and visual representation of crises enabled by new technologies of imagery and driven by a sense of sympathy for the suffering of others.

Humanitarianism, a term that came into everyday use after 1800, is an enduring theme in any crisis. It is a philosophy of practicing compassionate action, a morally benevolent way of responding to human suffering. But beyond the justification of alleviating suffering, humanitarianism tends to obscure the politics of a crisis in the name of an altruistic desire for the preservation of human lives.

My purpose here is to draw attention to a humanitarian media culture and the larger, historical framework through which it may be understood. This entails a discussion of the colonial roots of media-driven humanitarianism and a reflection on the evocative power of images that valorizes human suffering over questions of poverty and inequality. My context here are the famines in nineteenth-century India.

Similar to the famines in colonial India, COVID-19 is no mere accident of history. It is a story of spiraling inequality, rising poverty, and an escalating climate crisis that has inflicted damage on a scale rarely seen before. Moving beyond the obvious story of the pandemic – the overflowing hospitals, ventilator shortages, and infected healthcare workers – our current predicament raises some fundamental ethical questions on the relative value of human lives in contemporary society. “All lives are precarious,” the anthropologist Didier Fassin reminds us, “but certain lives much more so than others.” What makes this observation compelling to me as a scholar of colonial history is that it allows me to further examine the parallels between the current pandemic and the long history of famines in colonial India.

As the pandemic and its attendant humanitarian crisis unfolded in India, it gave rise to a slew of theories – from the scientific to the social – that bear resemblance to how misinformation spread during colonial famines. Predictably, in our media-saturated public sphere, television and social media have made sweeping predictions about the pandemic and sought the views of “experts” ranging from development economists, data analysts to celebrities – people in fields only tangentially related to epidemiology. This “epidemic of armchair epidemiology” as one scholar astutely observed, hinged on a media ecosystem in which public opinion could be manufactured, falsehoods amplified, and the trustworthiness of information determined by Facebook news feeds, Twitter trends and Google searches.

Pandemic media coverage in India was from the outset subsumed by images of a mass exodus of migrant laborers from the cities to the villages, triggered by a chaotically implemented lockdown. As police herded the migrants into 21,000 relief camps, the onslaught of images ruffled many viewers who took to social media with hashtags like “#MigrantLivesMatter,” declaring their sympathy for the plight of the migrants. The public visibility of the migrants moved the Indian middle-class, who until that point, seemed oblivious that migrant workers constituted the backbone of the informal urban economy and formed the logistical infrastructure of the industrial corridors across the country.

But the media overwhelmingly failed to report that the utter vulnerability of the migrants has much deeper roots – the consequence of uneven and unplanned economic development and urbanization. A typical instance of this urbanism is that of Rajarhat, a satellite township at the north-eastern fringes of Kolkata. It was imagined and instituted exclusively for the aspiring Indian middle class. What merits focus here is the “invisibility” of labor in Rajarhat’s urban development: of displaced farmers and fisherfolks, forced to sell their lands with little remuneration, and subsequently employed as cheap labor to the middle-class communities; and the new wave of migrant workers either servicing the gated enclaves or the booming construction sector.

Visual representations were not the only way of making sense of the pandemic. Commentators regularly drew upon a language of statistics – in the form of graphs and charts with percentages and curves – that revealed the qualitative aspects of human lives in neutral, scientific terms. Yet, despite this mania for pandemic-related data, photographic images undeniably succeeded in imposing a perception, albeit a misleading one, that the suffering was sudden and unpredictable rather than something emanating out of the existing structural inequalities that pre-emptively determined whose lives are valued most in our society.

If history is any indication, then the use of statistics in humanitarian crises should not come as a surprise. This fervor for numbers can be traced back to the famines in nineteenth-century India when the characterization of hunger, in statistical terms, was an issue of intense debate. Journalists were questioning the wisdom of government intervention in matters of famine policy based on hunger statistics. While the authority of statistics was undoubtedly growing in the late nineteenth century with the publication of imperial gazetteers, multivolume commercial dictionaries, and agricultural glossaries, they often carried less immediate weight than anecdotal evidence and personal observation.

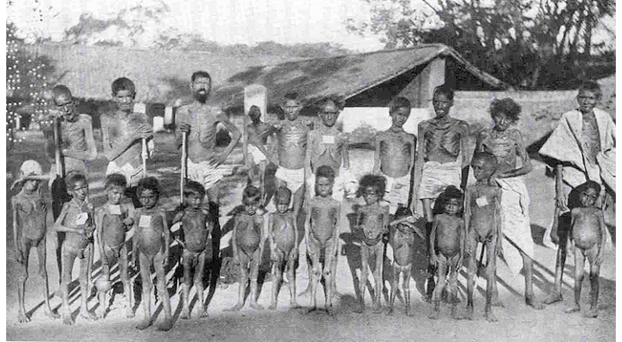

Especially revealing in this regard is the account of Julian Hawthorne, son of the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was appointed as the special famine correspondent of the Cosmopolitan magazine in India. While recounting his most “haunting experience” in an orphanage in Jabalpur in the Central Provinces in 1897, Hawthorne drew on a humanitarian language of sympathy instead of numerical data to create a persuasive image of hunger as a human condition rather than an abstract scientific problem.

Photographs lent a visual dimension to Hawthorne’s narrative that was instrumental in conveying the wretched conditions he observed in famine camps – women and children begging for food or lying in despair beside an empty plate, or reduced to scavenging for scraps along with dogs. Hawthorne combined eyewitness accounts with vivid images of the starving to make the suffering as real, immediate, and as disturbing as possible. Neither ethnographic nor picturesque, Hawthorne’s images soon became the focus of public attention as emblematic of the famine experience, generating a new-found interest in famines as a human tragedy.

Much like the recent images of migrant workers on social media, sympathy for the nineteenth-century famine victims was predicated on the distance between the spectator and the sufferer. Photographic technology, with its aura of objectivity and incredible mobility, offered a heightened sense of realism, making distant suffering seem quick and immediate enough to elicit powerful emotions from the viewers.

The use of photography accentuates compassion rather than offering an informed view about the structural context in which crises are produced and managed. If dominant media images of humanitarian crises teach us anything, it’s that they are being propped up to promote an emotional frame of reference unanchored in the historical realities of a crisis. The historical antecedents of the current crisis are crucial to understanding human vulnerability as a political question that is linked to long-standing forms of structural injustice. Concomitantly, the systemic dimensions of a crisis serve to highlight the asymmetry of power upon which we act towards vulnerable others.

Now, in the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s time to remind ourselves that the humanitarian endeavor is a political process governing lives through the act of saving. Only a commitment to political questions of justice and equality can determine whose lives are valued, in life and in death.

Bibliography

Chouliaraki, Lilie. 2012. The Ironic Spectator: Solidarity in the Age of Post-Humanitarianism. Polity Press, Cambridge.

Fassin, Didier. 2011. Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hawthorne, Julian. August 1897. “India Starving,” Cosmopolitan 23:4.

Lambert, George. 1898. India: The Horror-Stricken Empire. Berne, Ind: Mennonite Book Concern.

Anindita Nag is a cultural historian of modern South Asia, with allied interests in the history of science and technology, histories of food and famine, and visual culture in the modern world. Her scholarship has focused on the strategic engagement between science and imperial governance in India, particularly in the contexts of inequality, poverty, and resource scarcity. She is associated with the research group on “Colonial and Postcolonial Histories of Planning” at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin. Her ongoing research explores the cultural underpinnings of planning in the context of colonization, development, and humanitarian aid.

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science(Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)