Editors’ Note: This blogpost was written originally in May 2020.

On May 9, 2020, the total death toll from COVID-19 in Japan exceeded 600. Opinions have differed as to how this figure should be viewed, even within the country. The government has decided to extend its current state of emergency for the time being. At the same time, there are those who worry about the future of the Japanese economy and question the delayed return to normalcy.

In terms of the number of deaths, it is true that well over 600 people die in Japan every year from seasonal influenza and tuberculosis (as of 2018, the figures were 3,325 and 2,204 respectively). The number of deaths from pneumonia, though it has decreased slightly in recent years, is incomparably large (as above, 94,661). The fact that these diseases do not garner as much attention as COVID-19 pneumonia may seem inconsistent with the death toll.

The reasons for the curent low death toll in Japan are not known, and any hypothesis must wait to be verified at a later date. However, the reason for Japan’s continued cautious stance on COVID-19 seems to have something to do with its history of epidemics and their prevention. Over the last century, Japan had not experienced an epidemic of the sort that would affect its entire population. Since the Meiji era, the structure of disease has gradually shifted from acute to chronic diseases, and the initially draconian public health system has been reformed to be more conscious of human rights. This is the scene into which COVID-19 arrived and has been dealt with thus far with a wait-and-see approach.

What sort of infectious diseases has Japan experienced so far and what measures have been taken? Let’s take a brief look at the epidemics and the public health system in Japan since modern times.

The Origins of “Densen-byō 伝染病”

Infectious diseases that can be transmitted from person to person and cause a large number of deaths at once are called “densen-byō” in Japanese. The notion of “densen-byō” is relatively new in Japan, and seems to have been established in the late Edo period.

Prior to that, the word “densen” could be used to describe the spread of disease, but its meaning was limited to the phenomenon of similar physical symptoms being exhibited by people in close proximity to one another (In the late modern period, some physicians described smallpox and syphilis as “densen-byō” caused by the physical transmission of poisonous air, but this theory was hardly accepted at the time.).

It was the local epidemics of typhoid and cholera in the 1820s that had a major influence on the establishment of the concept of “densen-byō” in Japan. An outbreak of unknown diseases from Nagasaki, the window for trade with China and the Netherlands, made physicians aware that they came from abroad and prompted the translation of Western epidemiological books. When cholera spread again across the country in the 1850s, physicians vigorously experiment with various treatment methods used in the West, the origin of these diseases. The shogunate also took this opportunity to order professors at research institutes for Western studies to investigate the Western open port quarantine system in order to prevent the introduction of foreign epidemics.

The Expansion of the Public Health Infectious Disease Control System

In Japan, the public health system was designed from the Meiji era (1868-1912) with the prevention of infectious diseases, especially acute infectious diseases, as its top priority.

The first step was to prevent smallpox. Since smallpox had already spread in the Japanese islands, its suppression was to be managed through immunization policies. Legislation to require smallpox vaccination was promoted, and after 1876 it became compulsory for the whole population (the legal framework of compulsory vaccination was then continued in Japan for a century until 1976). Smallpox caused several epidemics with more than 10,000 deaths during the Meiji period, but after the Taisho period (excepting the post-war repatriation period), its spread was largely under control.

Other acute epidemics were initially dealt with separately. However, the 1879 cholera epidemic, which affected 160,000 people out of a population of 36.5 million and killed more than 100,000, prompted the enactment of the “Infectious Disease Prevention Law 伝染病予防法” (1880), which set in motion a full-scale countermeasure against the disease. This law designated six diseases – cholera, typhoid fever, dysentery, diphtheria, typhus, and smallpox – to be “Designated Infectious Diseases” and included comprehensive regulations regarding the notification, accommodation and isolation of patients, the disposal of dead bodies, disinfection, cleaning, quarantine, crowd prohibition and traffic stops.

New additions were made to the list of “Designated Infectious Diseases” every time a disease of particular importance appeared, with the addition of scarlet fever and plague in 1897, and paratyphoid fever and encephalomyelitis in 1922 (although the global epidemic of influenza that began in 1918 killed about 400,000 people in Japan, this epidemic was considered transitory and was not marked as a “Designated Infectious Disease”).

The system that constantly monitored and controlled the spread of these “Designated Infectious Diseases” kept the ratio of the deaths they caused to the total number of deaths at a very low level: from 1880 to the end of the war, that ratio exceeded 5% in only the first seven years (with the highest being 16%, or 150,771 people, in 1886, during a major cholera/typhoid/smallpox epidemic), and the remaining period experienced fluctuations of approximately 2% (around 20,000 people).

In contrast, a high percentage of the total number of deaths before the war were due to chronic infectious diseases, especially tuberculosis. This disease, known as “rōgai” from the early modern period, attracted attention in the middle of the Meiji era as an infectious disease that attacked factory workers, and in 1899, the number of deaths was surveyed nationwide for the first time. At that time, the number of deaths was already about 8% of the total number of people killed, but this figure gradually increased since then and reached 14% (171,473 people in 1943) by the end of the war. Tuberculosis sanatoriums were set up around the country, and after the “Tuberculosis Prevention Law” was enacted in 1919, control of the source of infection was strengthened. Yet, tuberculosis continued to be the leading cause of death from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Thus, Japan’s public health system for infectious diseases began with a focus on acute infectious diseases, and chronic infectious diseases were only added to its list from the middle of the Meiji era. However, while acute infectious diseases were generally treated with a high level of caution due to the human and social damage caused by epidemics, the treatment of chronic infectious diseases were differed depending on the disease. For example, pneumonia and gastroenteritis, which, along with tuberculosis, were among the top three causes of death before the war, were not given any particular attention.

The Prevention of Infectious Diseases in Post-War Japan

The pre-war public health policies for the prevention of infectious diseases was largely followed even after the war. Still, a notable change occurred in 1948, when the conventional “Smallpox Vaccination Law” (enacted in 1909) was abolished and a new all-encompassing “Vaccination Law” was enacted. With the enactment of this law, the number of diseases subject to compulsory vaccination was expanded at once to 12: smallpox, diphtheria, typhoid fever, paratyphoid fever, tuberculosis, typhus, plague, cholera, scarlet fever, influenza, Weil’s disease, and pertussis. The number of diseases has thereafter increased and decreased. (The BCG vaccine for tuberculosis was mandated separately in the “Tuberculosis Prevention Law”). The long history of smallpox control had led to the widespread adoption of vaccination as a method of ensuring public health.

However, due to frequent medical accidents and reported “side affects” to vaccines, each newly developed vaccine has undergone cycles of cancellations and resumptions. In the late 1960’s, when “adverse reactions” to the smallpox vaccine became a major social problem and lawsuits were filed against the state, the system of compulsory vaccination by law came to be reconsidered. In 1976, the penal provisions of the “Vaccination Law” were abolished, and vaccinations were recategorized into those “recommended” by the state and those that were “optional”. The following year, in 1977, a system was established to provide relief for those whose health had been damaged by vaccines. These people-centric reforms to the vaccination system have continued to the present day.

These people-centric reforms of late have also been applied to the state’s methods of regulating public health by way of quarantine, traffic stoppages and the suspension of transportation. In 1998, the “Infectious Disease Prevention Law 伝染病予防法”, which had been the main legal basis for Japan’s response to infectious diseases, was abolished, and a new “Infectious Disease Prevention Law 感染症予防法”, based on the principle of respect for human rights, was enacted. The law classifies infectious diseases into eight categories according to the severity of symptoms and infectiousness of the pathogen (see the table below), and the response to each category varies in great detail.

| Class I Infectious Disease | Smallpox, Plague, Lassa Fever, … |

| Class II Infectious Disease | Polio, Tuberculosis, Diphtheria, MERS, SARS, … |

| Class III Infectious Disease | Cholera, Dysentery, Typhoid Fever, Paratyphoid, … |

| Class IV Infectious Disease | Malaria, Typhus, Japanese Encephalitis, Rabies, … |

| Class V Infectious Disease | Influenza, AIDS, Syphilis, Measles, … |

| Novel Influenza Infection | Novel Influenza |

| Designated Infectious Disease | COVID-19 |

| New Infectious Disease |

―― |

The “Designated Infectious Diseases” with which COVID-19 has been categorized are those that show characteristics of Class 4 or 5 diseases, but can potentially cause human and societal harm to an unprecedented extent. In other words, the category into which COVID-19 has been placed is rather ambiguous: on one hand, it indicates that the disease in question follows patterns similar to those seen in other diseases that have previously been dealt with in Japan, and on the other, it implies that the risk involved is hard to estimate and the measures taken may vary on a case-by-case basis.

We have briefly traced the history of epidemics/infectious diseases since modern times and the history of epidemic control up to the present day. It seems that Japan will be forced to face this particular “Designated Infectious Disease” for some time to come. Though there is some demand for a vaccination, it is unclear how far it can be utilized as a public health measure, given recent concern over “side affects” to vaccines. When the path ahead remains as unclear as ever, in what ways will we endure the current atmosphere of uncertainty? Japan seems to have its own unique struggle that cannot be reduced to the number of deaths.

The Sanitary Revolution in the Early Meiji Period

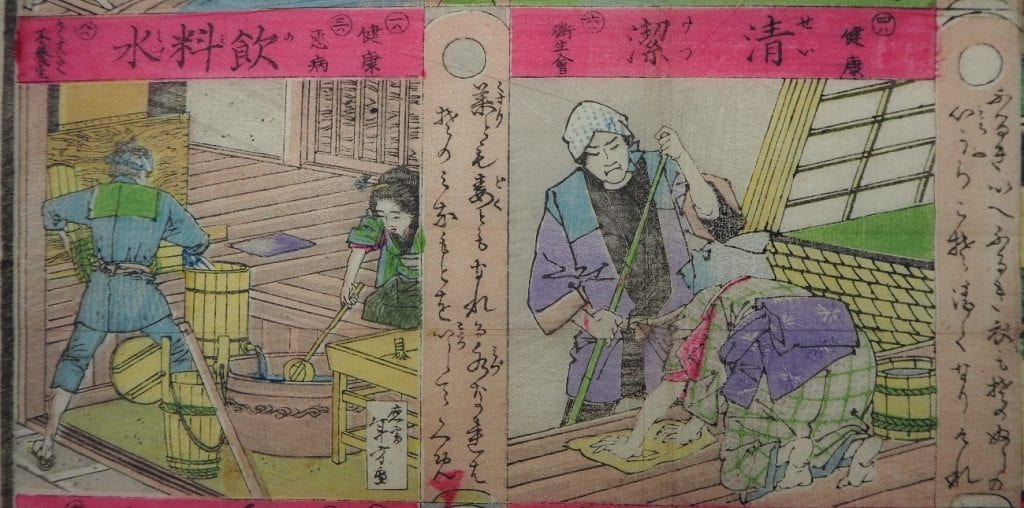

A board game (sugoroku) published soon after the enactment of the “Infectious Disease Prevention Law”. The Great Japan Private Hygiene Society, which had been established in 1883, created this game for the education of the public. Starting at “birth”, players must move through the following squares according to the roll of the dice to reach the end (happy and long-lived life): “smallpox vaccination”, “kindergarten”, “school”, “hospital”, “work”, “filth”, “exercise”, “nourishment”, etc.

Here are the cells for “cleanliness” and “drinking Water”. The book persuades people to keep their homes clean and drink clean water, explaining that most illnesses are caused by unsanitary living conditions.

Toyoko Kōzai is a researcher specializing in the history of medicine and medical sociology, and is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at Bukkyo University in Kyoto. Her research examines the history of health policies surrounding medical hygiene and anatomical donation (such as body, organ, and blood donation) in hopes of seeding further analyses of medical practice and bioethics in contemporary Japan.

Related:

近現代日本における伝染病と公衆衛生制度 :: 香西豊子 (日本)

The Japanese Islands and Infectious Diseases :: Toyoko Kozai (Japan)

Locating the Risk on Foreign Shores: The Making of “Covid-Safe” Japan :: Elizabeth Maly (Japan)

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)