This is the final part of a series on overcoming disruptions to teaching languages by seizing upon an opportunity to study the history of pandemics. Part I by Yuta Hashimoto is available in Japanese and English. This Teaching Moments series is co-presented by the MPIWG History of Science ON CALL project and the Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective.

Voices from the past

It has been now a month since the inception of the project, and I have been checking quite a few transcriptions. This has enabled me to read good chunks of the texts this project its tackling. Measles, smallpox, and cholera were an avoidable part of the daily life of early modern Japan. The horror that accompanied these diseases is well showcased by the 1858 Chronicle of the Cholera Pandemic (Korori ryūkōki 箇労痢流行記). The introduction touches upon an outbreak of fever that hit the city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo) in 1716 causing the death of 80.000 people in less than one month. The human tragedy is made palpable by describing the inability to give a proper burial to all these victims. A shortage of coffins led people to use empty barrels to bury the bodies (fig. 10), but, for those who could not afford any of this, the fate was even more tragic: they ended up wrapped in straw mats and thrown into the sea at Shinagawa. The same foreword tells us that the wave of cholera afflicting Japan at that moment yielded similar outcomes. The present reminds of the past and the past informs the present.

Reading this passage, I could not stop thinking about what happened to my hometown in Northern Italy, Bergamo, during the first month of the Covid-19 pandemic. The number of deaths was so high, that the army had to be called in helping to transport the cadavers to other municipalities to be cremated. Only after a few weeks the ashes were given back to families, together with a pricy bill.

How can we survive the trauma of these dreadful experiences? Early modern Japanese books and prints designed for the popular consumption give two answers to this timeless question.

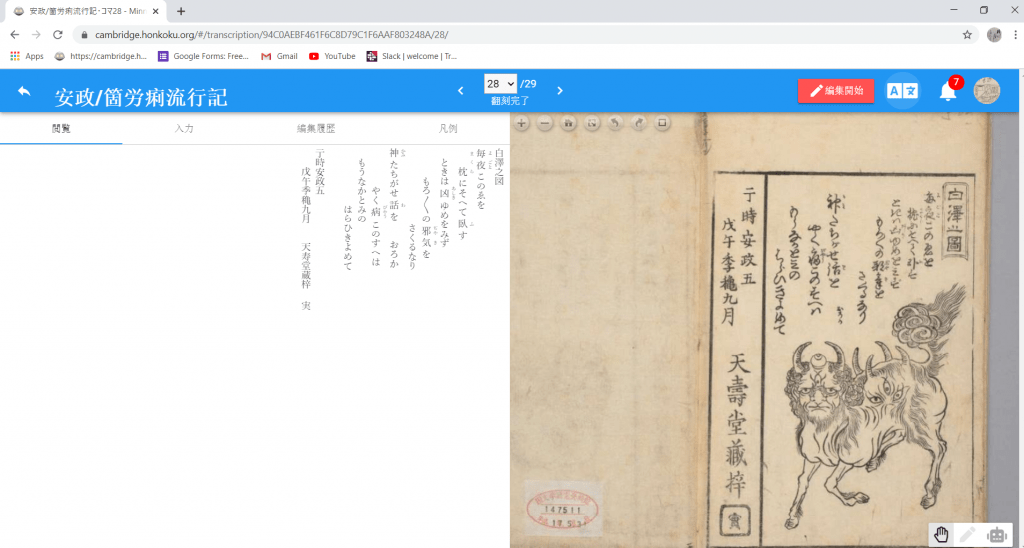

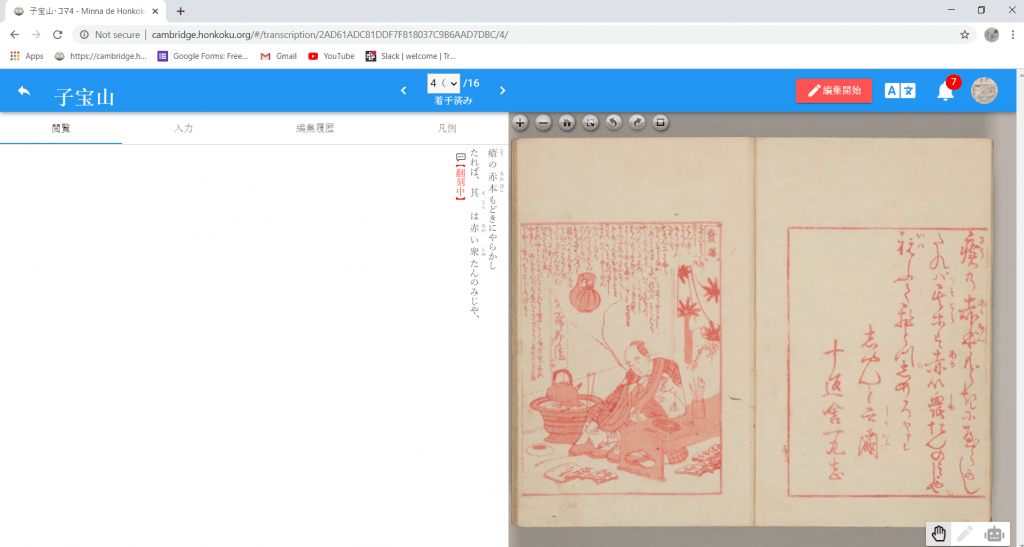

First, they ask readers to find some comfort in the belief that something supernatural will work out some magic. Chronicle of the Cholera Pandemic closes with the image of the deity Hakutaku, explaining that if you sleep putting this image next to your pillow, you will be protected from any evil, including that of virulent diseases (fig. 11). The 1803 The Mountain of Treasures for Children (Kodakarayama 子宝山)—written by one of the most successful popular writers of the time, Jippensha Ikku (1756–1831), and illustrated by Keisai Eisen (1790–1848)—not only embodies apotropaic power by being printed with red ink (fig. 12). It also fills us with hope with a story that sees the toys that children love so much mobilizing to convince the Smallpox Demon to spare lives. Call it superstition or popular belief, what these stories offer is some form of optimism, promising the triumph of life over death. It might sound rather simplistic for many of us, but we cannot deny the healing power that such heartening narratives can bear.

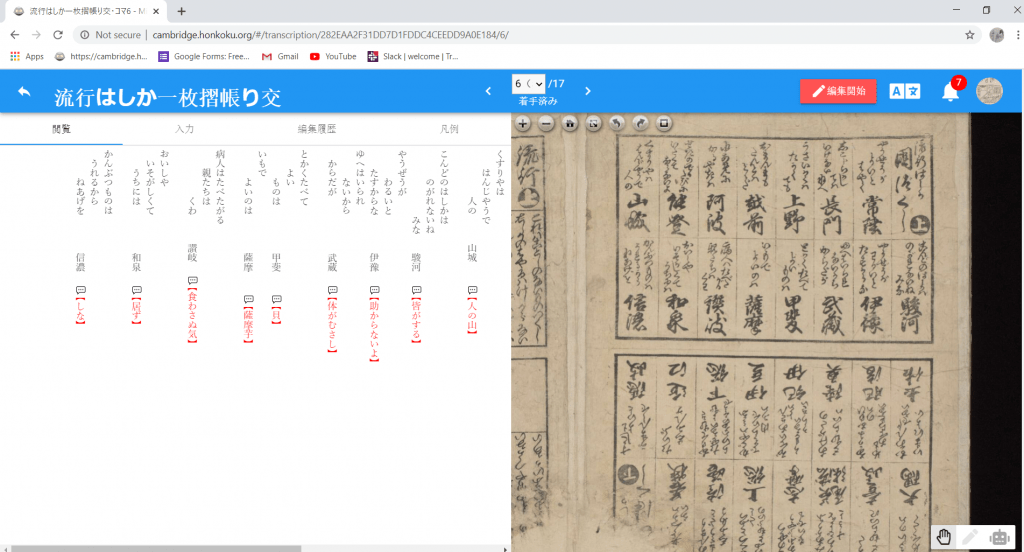

The second aspect that emerges from these publications is a desire to use laughter to defeat evil, as noted by Japanese scholar Tomizawa Tatsuzō. Some ephemera included in the project are organized around riddles and jokes. In a charming album that assembles measles-related ephemera preserved in the library of Keio University, we find a small-size print that lists famous places in Japan by asking readers to solve riddles constructed around measles (fig. 13). The second last (in the transcription) reads something that, if translated freely, would go as: “Doctors continuously on-call; their house: SAHARA DESERT.” In Japanese the play of word is on the place name Izumi, including the word izu meaning “not to be (at home).” If the idea that we can laugh when talking about deadly illnesses might sound anathema, another small print (yet to be added to the project) might sound even more irreverent, combining measles and sex as I present in the video: “Early Modern Japan and Measles: Acquiring Antiquarian Materials” (from 17.31).

I would imagine that I am not the only one feeling slightly uneasy at the combination of laughter and pandemics, even though I am aware that jokes are not necessarily alien to disaster narratives. Elliott Oring, for example, has studied the cycle of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. Will we ever be able to “laugh off” what Covid-19 has brought to humankind? Will our wounds ever be healed enough for us to joke about it? Will any of the literature that surely will be produced in Japan and more broadly around the world in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic embrace this light-hearted approach to trauma? Or are human beings not able to laugh off evil any more in the contemporary world?

There many more pages I need to check as part of the transcription project “Tackling Pandemics in Early Modern Japan.” I am excited at the prospect of what they will unveil both in terms of palaeographic challenges and intellectual discoveries. The greatest comfort is that I am not alone in this journey: the thirty-five participants and Prof Hashimoto are my invaluable companions. Lockdown measures might keep us physically apart but we are always united in the hunger for knowledge.

Suggested Readings

Gramlich-Oka, Bettina. “The Body Economic: Japan’s Cholera Epidemic of 1858 in Popular Discourse.” East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine, no. 30 (2009): 32-73. Accessed July 5, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/43150752

Oring, Elliott. “Jokes and the Discourse on Disaster.” The Journal of American Folklore 100, no. 397 (1987): 276-86. Accessed July 5, 2020. doi:10.2307/540324.

Smits, Gregory. “Warding off Calamity in Japan: A Comparison of the 1855 Catfish Prints and the 1862 Measles Prints.” East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine, no. 30 (2009): 9-31. Accessed July 5, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/43150751

Rotermund, Hartmut. Hōsōgami, ou la petite vérole aisément: matériaux pour l’étude des épidémies dans le Japon des XVIIIe-XIXe siècles. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, 1991. [also available in Japanese]

Rotermund, Hartmut. “Illness Illustrated: Socio-Historical Dimensions of Late Edo Measles Pictures (Hashika-e).” In Written Texts Visual Texts: Woodblock-Printed Media in Early Modern Japan, Susanne Formanek and Sepp Linhart, eds. Leiden: Hotei, 2005, pp. 251-282.

Tomizawa Tatsuzō 富澤達三. Nishiki-e no chikara 錦絵のちから. Tokyo: Bunsei shoin, 2005.

Laura Moretti is a Senior Lecturer in Pre-modern Japanese Studies at the University of Cambridge and Fellow at Emmanuel College. Her research focuses on early modern popular prose; the history of the commercially printed book; the interaction of text and images; and early modern paleography. Her publications include Recasting the Past. An Early-modern Tales of Ise for children (Leiden: Brill, 2016). Forthcoming in December 2020: Pleasure in Profit: Popular Prose in Seventeenth-Century Japan (New York: Columbia University Press).

Related:

Rethinking Normalcy :: Zheng Guan (United States)

Teaching the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Colorado Plateau :: Daniel Burton-Rose (United States)

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)