This is second of a multi-part series on overcoming disruptions to teaching languages by seizing upon an opportunity to study the history of pandemics. Part I by Yuta Hashimoto is available in Japanese and English. This Teaching Moments series is co-presented by the MPIWG History of Science ON CALL project and the Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective.

Teaching Japanese early modern palaeography in normal times

Every year in August Emmanuel College (Cambridge, UK) welcomes around thirty scholars for the Summer School in Japanese Early Modern Palaeography. Graduate students join more seasoned academics, museum curators, and librarians driven by the same desire: to learn how to decode Japanese early modern documents.

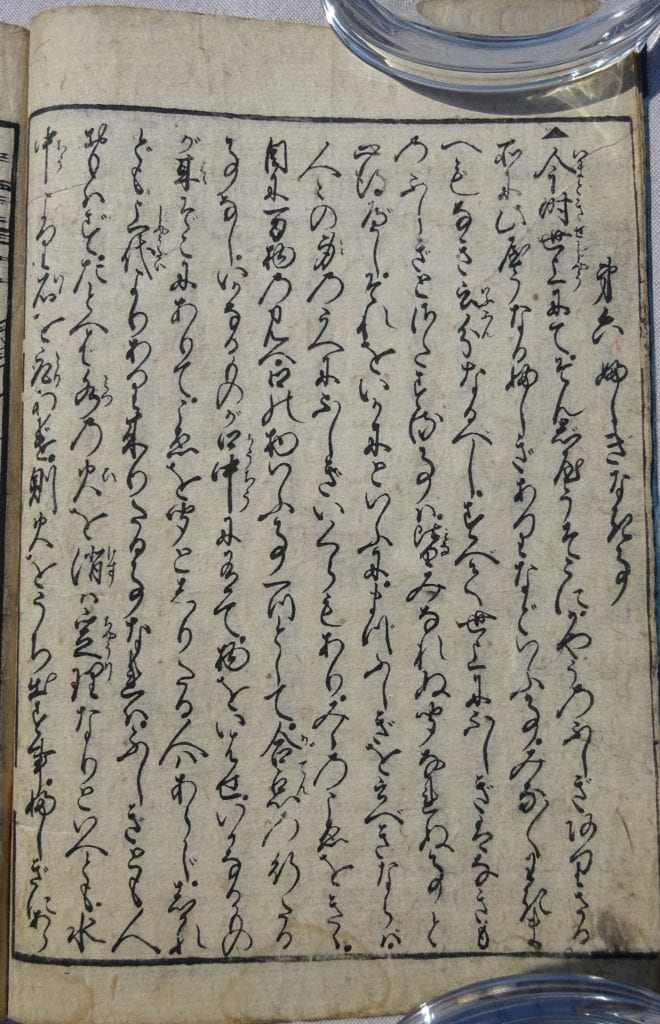

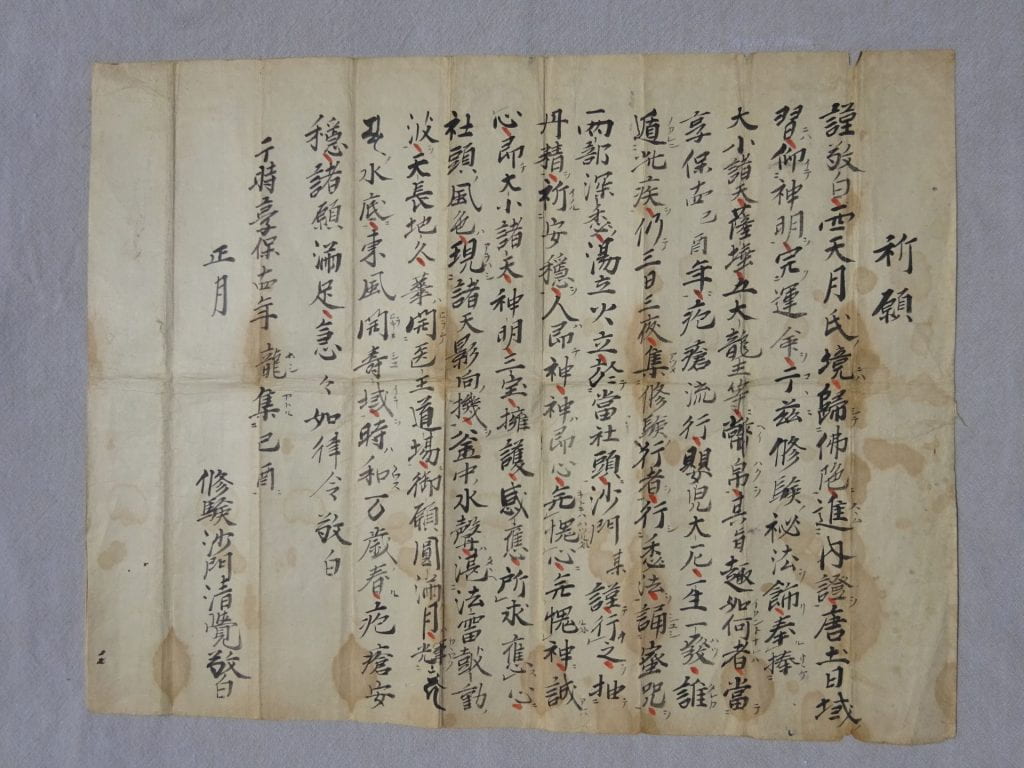

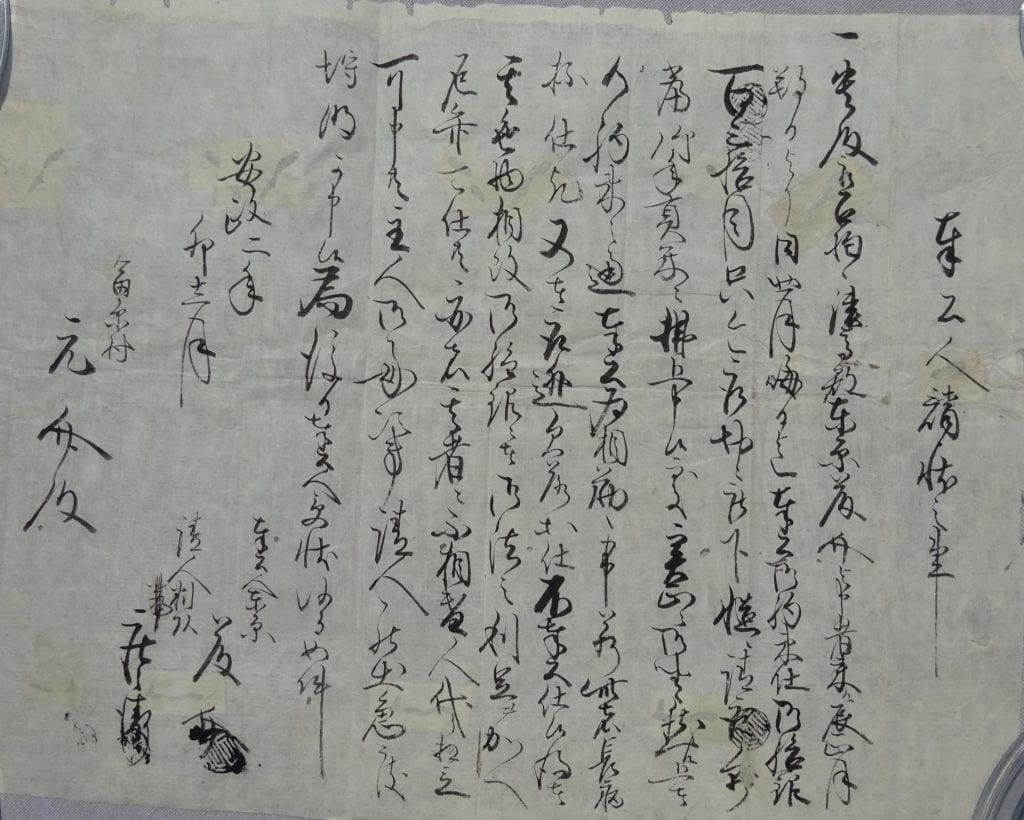

Accessing Japanese printed books and manuscripts produced in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries entail several linguistic and palaeographic challenges. Texts in the vernacular were written in the usual mixture of logographic characters (kanji) and phonographic syllabary (hiragana) but the cursive nature of the script and the use of multiple visual variants for the same hiragana syllable make them unintelligible to anyone who does not have adequate palaeographic training (fig. 1). Moreover, a wide range of texts used classical Chinese (fig. 2) or a hybrid artificial language known as sōrōbun (fig. 3). These require knowledge of how these written idioms work. Our summer school is conceived as an intensive course that equip participants with the skills required to read such primary sources.

The atmosphere in class is vibrant. Pair and group work create a dynamic learning environment, where everyone has a voice. Dividing learners in smaller clusters normally requires careful thinking and enables a variety of patterns: when students of similar levels work together, what appears at first sight as a scary bunch of squiggly signs turns into something more manageable; intermediate and advanced readers help beginners to make their way into complex forests of signs; and those whose decoding abilities are already good can enjoy munching through long chunks of text. The teaching staff plays an active role in fostering in-depth understanding and accuracy in the process of reading and transcribing. Every 90-minute session closes with a half-an-hour interactive lecture where I explain the most arduous palaeographic challenges of each text. My colleague Prof Yamabe Susumu (Nishogakusha University, Tokyo) explains all the ins-and-outs of reading classical Chinese in a friendly manner. London-based calligraphy master Yukiko Ayres brings to life the movements of the brush used to write these texts (fig. 4). We take pride in giving all participants detailed feedback. Walking around the classroom and checking the transcriptions that are being produced allows me to gauge how each of my students is progressing throughout the two weeks. Even though we normally deal with a fairly large group, I strive to give them personalized guidance, very much in the spirit of the supervision system that characterizes the teaching philosophy at the University of Cambridge. Human interaction is the key, inside and outside the classroom. Coffee breaks, lunches on the College paddock (when the British weather allows it!), pub and college dinners become occasions to exchange ideas, share experiences, discuss projects, and make friends.

What happens when a pandemic of the proportions of Covid-19 hit? International travel is jeopardized, institutions of higher education have temporally closed their buildings, and the government guidelines call for more or less strict social distancing measures. We had little choice but to postpone the seventh summer school until next year, hoping that the world might return to normal at that stage.

A Covid-19 compatible alternative

Yet, none of us were ready to simply call it quits. The participants who were selected for the 2020 programme were eager to be granted a learning opportunity notwithstanding the Covid-19 pandemic, and we were equally committed to keep our young scholars engaged with the early modern world beyond their specific research projects. What I had learnt about remote teaching during the third term at Cambridge, however, was of little help. While synchronous seminars on Zoom turned out to be quite effective when teaching our cohorts of undergraduates and when holding 1:1 supervisions with my graduates, how could I successfully replicate this model with some of the participants living on the West Coast of the United States and some others based in Japan? How could I protect everyone’s wellbeing by not forcing some to work at ungodly hours in the dead of the night? How could I overcome the “Zoom fatigue” that inevitably emerges after hours of joining classes via a computer screen? Asynchronous lectures might have been welcome by total beginners but would have killed the joys of promoting a form of pro-active and empowering learning experience for the more experienced.

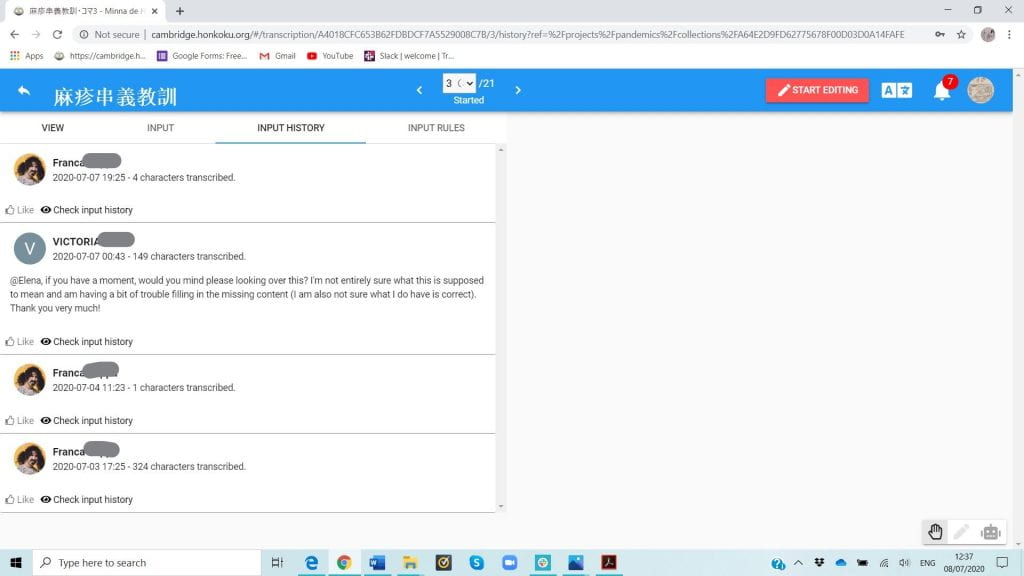

After a few weeks spent agonizing over what to do, I realized that the answer was in the collaboration that I had envisaged for quite some time with Prof. Hashimoto Yuta and his transcription platform Minna de honkoku. This cleverly designed online platform enables a group of people to access Japanese premodern and early modern texts in digital format and to transcribe them with the aid of Artificial Intelligence (AI). The beauty of Minna de honkoku is manifold: its design is extremely user-friendly and intuitive thus not requiring the user to be an IT wizard; AI gives the transcriber reading hints; collaborative work is encouraged but each contribution is dutifully acknowledged and recorded (fig. 5). What is more, Prof Hashimoto is deeply passionate about his work: he is keen to gather constructive feedback and to channel it into developing his platform further.

Galvanized by Prof. Hashimoto’s enthusiastic response to the idea of collaboration, I needed to identify a theme. That did not prove too arduous, though. Inspired by a thought-provoking exchange of ideas about the topic of pandemics in early modern Japan shared on the mailing list of Premodern Japanese Studies (PMJS) and by the video “Japanese Classics in a Time of Contagion” released by the Japanese Institute of Japanese Literature when the lockdown started in the UK, I decided to work with texts that dealt with major pandemics that hit early modern Japan: smallpox, measles, and cholera. Not the serious medical stuff, though. I was interested in reading what early modern commercial publishers printed and marketed for the popular reader. Illustrated books, colourful woodblock prints, and a whole range of small-size ephemera.

Guided by a few books and articles published in English and Japanese on this subject, I foraged the digital archives in search of images that could be readily used. I also purchased some primary sources from the website Nihon no Furuhon-ya (administered by the Japanese Association of Dealers in Old Books) thanks to a generous donation from Mitsubishi Corporation International (Europe) Plc. I also received a splendid gift of three measles prints (hashika-e) from New-York based antiquarian dealer Jonathan Hill Bookseller. The Victoria and Albert Museum and a private collector based in the UK joined forces, allowing us to use some of their materials. The partnerships and friendships developed over the years through the summer school work proved invaluable when devising a way forward amidst Covid-19. In a few days I had put together an interesting group of Japanese printed books and ephemera produced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Most of these materials survive only in their original format and await transcriptions. The few that have been already transcribed are in books that are not retrievable in Open Access format. Yet the majority of scholars interested in the topic of pandemics would need transcriptions to conduct research. And this, in turn, makes our efforts worthwhile: providing access to primary sources that might not be otherwise acknowledged.

Laura Moretti is a Senior Lecturer in Pre-modern Japanese Studies at the University of Cambridge and Fellow at Emmanuel College. Her research focuses on early modern popular prose; the history of the commercially printed book; the interaction of text and images; and early modern paleography. Her publications include Recasting the Past. An Early-modern Tales of Ise for children (Leiden: Brill, 2016). Forthcoming in December 2020: Pleasure in Profit: Popular Prose in Seventeenth-Century Japan (New York: Columbia University Press).

Related:

Rethinking Normalcy :: Zheng Guan (United States)

Teaching the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Colorado Plateau :: Daniel Burton-Rose (United States)

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)