“Wash your hands with soap for 20 seconds” is a measure whose effectiveness above all other methods of preventing infection is advertised these days from the left and right, from the north and south, regardless of industry and nationality.

Handwashing is a key step in both disinfection and the antiseptic method—that is, the act of resorting to chemical or physical processes to put “dead or living material into a state that it cannot infect.” In the latter, in addition to the hygienic and surgical disinfection of hands, the antisepsis of the skin and the disinfection of surfaces, instruments, laundry, rooms and waste are added.

A simple and universal gesture, many will think about handwashing; forgetting, first, the privilege of having clean water and, second, that behind its humbleness lies the artificial side of this exercise, which, like everything human, had to be learned and accepted before it became a private habit. This is one chapter in the ambivalent history of dirt and cleanliness in the Western world, summarized by Canadian writer Katherine Ashenburg in The Dirt on Clean, a 2007 bestseller. In fact, handwashing is a health measure that originated in Austrian hospitals in the mid-19th century, beset by puerperal fever, one of the main causes of maternal and hospital mortality.

Uterine infections, needless to say, predate the human species, predate the clinics and poor conditions of industrial societies; there is the long and varied list of rich women who died shortly after giving birth, starting in ancient times and ending not so long ago. But in traditional childbirth, as practiced for centuries—at home, by midwives—the incidence of puerperal fever was rare. Particularly in comparison with what happened from the 17th century onwards, when, with the growth of European cities and poverty, the number of women resorting to charity and philanthropic hospitals to give birth anonymously and subsequently deliver their newborn babies to attached orphanages increased. Cases of this fever, however, exploded with the passage of control of child deliveries and from congregation hospitals to doctors.

In 1659, the Englishman Thomas Willis would baptize the illness as febris puerperarum, which was described shortly afterwards by the Frenchman François Mauriceau. At the beginning of the 18th century, puerperal fever was considered an “essential” fever: that is, a post-partum disease, triggered by “contagion” or, according to other experts, by “infection”—that is, by the poor quality of the air or the miasmas of the poor neighborhoods and crowded hospitals. In the former case, the fever arose from being in the same room or even in the same bed, of those who, healthy or with a fever, had given birth or were about to give birth. In 1795, Alexander Gordon, a physician in Aberdeen, suggested that this fever was transmitted from one bed to another through caregivers, recommending measures to reduce its frequency but encountering disdain from his colleagues.

Thanks to autopsies, puerperal fever began to be understood as the inflammation of the uterus or peritoneum, but at the same time it became the epidemic scourge of Europe’s maternity hospitals, killing nearly 20% of women in large hospitals and 70% of patients in smaller maternity hospitals. However, these figures had only a marginal impact on the general epidemiology: the vast majority of women continued to give birth outside these institutions.

However, the disease was advancing. And it was advancing through the spaces of the hospital, following the path that connected the dissecting room with the delivery room, in a circuit where the same hands and instruments that auscultated corpses and palpated the sick, assisted the women in labour. In 1843, the American doctor Oliver Holmes put forward the thesis that doctors and nurses transmitted the disease and recommended hand washing. Four years later, the Austro-Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis tried to prove that the whole affair lay in the poor hygienic conditions of the hospitals, in the lack of cleanliness and in disinfection on the part of the doctors. To this end, Semmelweis compared the deaths of two obstetric departments at the General Hospital of Vienna, isolating one, and concluding that “the unknown cause of such horrible devastation lies in the dissection of corpses, whose remains remain attached to the hands of the dissectors.”

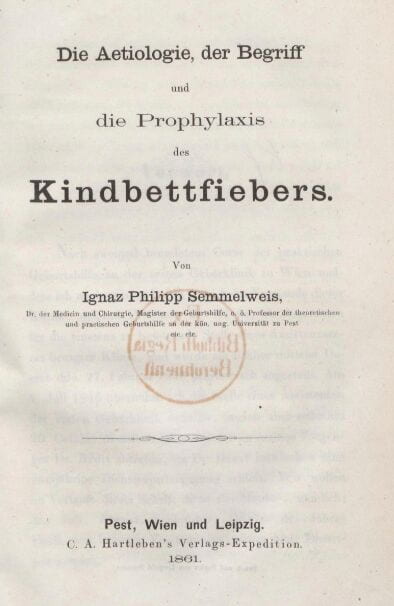

This iatrogenic catastrophe, one of the most important of the 19th century, occurred at the same time that the so-called New Viennese School was flourishing under the direction of the pathologist Karl Rokitansky, who placed the dissection room at the centre of medical studies. It is not surprising that pathologists, including Rudolf Virchow, a champion of social medicine, disregarded the conclusions of Semmelweis, who, annoyed by this rejection, in 1860 published “The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Puerperal Fever,” attacking Virchow, already famous for his cellular pathology.

Based on his experience accumulated in 15 years of work in three different institutions, Semmelweis considered that childbed fever, without exception, was “a fever of reabsorption, caused by the absorption of a decomposed organic animal substance brought to the individual from the outside,” causes that—contrary to autoinfections—could be prevented. The “poison” came from the corpses that the students used to learn how to cure. It did not matter the age, gender, previous illness, or whether the body was a man or a woman who had not yet given birth. The only relevant question was the degree of putrefaction. The finger that examined a cervix that was emaciated by cancer, carried the organic substances of the surgical cure or of the anatomy lesson to the cervical parts of the woman in labour,

Semmelweis, in Vienna, began demanding that midwives, doctors and students wash their hands with diluted chlorine to rid them of these decomposed substances. However, there was another danger. The fact that children of mothers with milk fever did not get sick synchronously proved that the infection did not occur during birth. He therefore pointed also to the tools and bedding of the postpartum period: the sheets contaminated with the loquia. This vaginal secretion of blood, mucus and placental tissue, normally produced up to four or six weeks after birth, was lethal, especially in winter when the sheets were barely washed and women who had just given birth, wrapped in them, rested their genitals, damaged by the birth, on these decomposed substances.

Water and chlorine, for the hands and the sheets, managed to reduce mortality in Vienna to a minimum. Meanwhile in Berlin, governed by the ideas of Virchow, professor of pathology and prosector [the skilled preparer of dissected corpses for medical education] of the Charité since his appointment in 1856, fever took more than twenty women in the early winter. “Since 1847,” said Semmelweis, “there is nothing more frightening than the ignorance with which the obstetric education about post-partum fever continues to develop.” So much so that in 1896 a textbook still spoke of “foreign substances” present in a woman’s body that “fermented” during birth. It was only at the beginning of the last century, when the existence of pathogens was accepted after the work of Robert Koch, Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister, that disinfection and hand washing became part of common sense, and part of a now sacrosanct practice for medical professionals. Our normal has a frightening history, but one that reminds us that with soap and water, the future is still in our hands.

Translated from the Spanish, under a different title, from Irina Podgorny, “Breve historia de Las manos limpias,” Revista Ñ, 4 April 2020, 9.

Irina Podgorny is a permanent research fellow at the Argentine National Council of Science (CONICET) at Museo de La Plata, Argentina. She studied Archaeology at the La Plata University, obtaining her Ph.D. in 1994 with a dissertation on the history of archaeology and museums. She has been a research fellow at the MPIWG Dept. III Rheinberger (2009–10), she was also a postdoctoral fellow at Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut Berlin and at MAST (Museu de Astronomia) in Rio de Janeiro. Irina’s current research project deals with historic extinctions and animal remedies. At the MPIWG she is also a member of the Body of Animals Working Group in Dept. III. In addition to her academic research, Irina collaborates with Argentine cultural weeklies and Latin American artists, most recently for a 2018 art exhibition in Lima, Perú. She has been a member of the Editorial Board of Science in Context since 2003 and History of Humanities since 2017. She is the current president of The History of Earth Sciences Society and has recently been elected to the Council of the History of Science Society. Her current work focuses on the history of paleontology, museums of natural history, archaeological ruins, and materia medica. Her publication can be consulted at https://arqueologialaplata.academia.edu/IrinaPodgorny

Related:

Lavarse las manos: Un gesto nada humilde :: Irina Podgorny (Argentina)

Historias de papel (higiénico) :: Irina Podgorny (Argentina)

A Story about (Toilet) Paper :: Irina Podgorny (Argentina)

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)