The Teach311 + COVID-19 collective and the History of Science ON CALL project are pleased to co-present this e-mail interview from March 31, 2020 with historian Indira Chowdhury about the role of the humanities in understanding and dealing with the current pandemic. We are grateful for these insights about the role of public history methods and oral history archives to study the cross-generational effects of pandemics and disasters more generally, be they famines or factory explosions like Bhopal. Chowdhury is the Founder-Director of the Centre for Public History at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru, India.

1) Using your perspective as a scholar of oral history, could you please unpack a current development or dilemma with regards to the present pandemic?

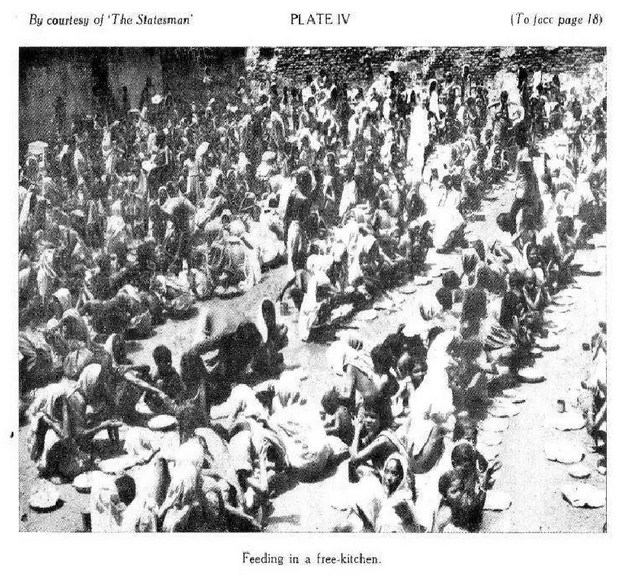

In India, particularly in Bengal where I come from, the memory of food shortage during the man-made famine of 1943 is so strong that as children we were asked never ever to waste food. The memory of people dying of starvation on the streets begging for “rice water” is a scary and compelling image. It haunted my elders and created the base for learning about being frugal with food, never waste. It also created in my generation a sense of panic whenever there are natural disasters or shut-downs of the kind we are experiencing now. Instead of encouraging people not to hoard food, these memories have taught a lot of the middle-class to stock up or hoard grains and other non-perishable items. And yet, the same haunting memory has incited empathy for those who have nothing and live on pavements. At this moment, we have students in my former university, Jadavpur in Kolkata, distributing hand sanitizers and disinfectants to communities, market places, to menial laborers, delivery boys and traffic police. Since there are about 100-150 people who live on the streets with no access to food, water or sanitation, the students have started cooking in a makeshift kitchen in the parking lot and are distributing one meal to the homeless people. This action is inspired as much by the past as by the present. While doing oral history interviews about Jadavpur University’s first Vice Chancellor, Dr. Triguna Sen (who by the way, did his doctoral studies in Munich), I recorded the earliest students telling us about how they served food to the refugees from the Partition of India in 1947. Not only did they cook and take food for the displaced refugee population who were at the Sealdah Railway Station, they also designed and fabricated trolleys at the university workshop to make the distribution more efficient.

As an oral historian, I have learnt a lot about how people remember disasters and epidemics of the past, how memories haunt them and how they see the reflections of the past in the present. Many of our fellow oral historians talk about the basic humanity of our craft – the need to understand how human beings confront crisis. At this moment, I am thinking of my interviews with Patachitrakars or scroll painters from Bengal who had painted scrolls about 9/11. When asked why they chose to tell stories about a disaster so remote they answered that they knew what it meant to suffer and lose loved ones, their creation of scrolls about 9/11 was therefore undertaken because they had great empathy and understood human loss. Indeed, one of the first phone calls that I got to express concern was from one of the scroll painters who called from his village to ask if we were alright in Bangalore.

The oral historian can at the time of COVID-19 outbreak understand how people cope with new demands that a highly contagious virus makes on them via the state and the medical system. The fear in India has been about the virus spreading within the community and there has been a total lockdown. Those most affected by this are the pavement dwelling poor and the migrant workers who have been walking unbelievable distances like 200-300 kilometres without food or water to reach home. At this point, many of us can only donate money to volunteer groups that are trying to feed them. Oral history projects which aim to understand what this kind of uncertainty meant for them physically, mentally and socially can only happen later. Again, this is how oral historians have worked in the past on disasters. The Bhopal Gas Tragedy happened in 1984; but oral histories of survivors were conducted almost three decades later and placed in the Remember Bhopal Museum in 2014. Oral history interviews with Bhopal gas tragedy victims were analyzed by Suroopa Mukherjee in her book, Surviving Bhopal: Dancing Bodies, Written Texts, and Oral Testimonials of Women in the Wake of an Industrial Disaster (Palgraves, 2010). The book and the oral histories in the Remember Bhopal Museum done by Rama Lakshmi alert us to the sheer unpreparedness in India for large scale disasters such as Bhopal. The present COVID-19 crisis is similar.

Oral history is one of the primary methods used by public historians all over the world. In the context of the current crisis, the practitioners of public history need to do two things with a sense of urgency: a) document the present crisis and b) archive the memories of those who have been through similar crises in the past so we can learn from collective experience.

2) What are the biggest intellectual puzzles or personal challenges that the current crisis raises for researchers like you?

The biggest intellectual puzzle for me has to do with memory – what remains in collective memory about disasters and epidemics of the past? Do we forget because the epidemics of the past were very different and so far back in the past that they are “erased” from public memory? In the context of India, I can say that memories of epidemics and pandemics of the past remain in collective memory in different forms – the cemetery in Park Street, Calcutta, now Kolkata is full of graves from colonial times that are of children, women and men who died of influenza. In Bangalore, we have a temple to “Plague-Amma” – goddess of plague. The area called Malleswaram was built as a planned suburb in British India after the Great Plague of 1898. Local stories that we have encountered in the course of oral history projects undertaken in Malleshwaram by students we have trained, mention how households would write on their doors in Kannada, words addressed to the Plague Amma, “Plague Amma! Nale ba” – “ Plague Goddess! Come tomorrow” – meaning, do not come to our house today. The next day, the Plague Goddess would encounter the same words and would thus eternally defer her attack! These are apocryphal stories but give us an insight into what has remained with the community after a hundred years. The temple to “Plague Amma” is like any other temple to the goddess, but this temple is to a new goddess – the Goddess who protects from Plague. It is believed that the plague of 1898 was transmitted through the Railways. In some ways the attribution of modern modes of transportation to spread of disease informs the decision by several governments to stop air travel to curtail the spread of COVID-19. A related intellectual puzzle would be – how do we understand the relationship between new technologies of transportation and the spread of new diseases?

3) Tell us about your research process. How has your research depended upon or contributed to collaborations? What kind of collaborations have these entailed (intellectual, educational, artistic, community)?

My oral history work has been across class and community. I have worked with poor artisans such as scroll painters as well as with people who are part of established scientific institutions. I have done a lot of oral histories with scientists who have spoken about the difficult circumstances in which they did their science. My research process depends on community level collaborations and collaborations with institutions. I have not done oral history research specific to disease or disasters. However, since I use a life story approach, my long interviews give us interesting insights from a range of experiences of people about disasters to technological changes. The archival oral histories that oral historians have created will be useful to later generations.

4) What does the current crisis illuminate about the role of the humanities research?

While scientists are struggling to create test kits for efficient testing and also working on a vaccine, the role of humanities research has not been discussed much in media. It is humanities research that can help us understand how people respond to disease and new modes of coping with pandemics. Humanities research also enables us to look at people’s experiences and understand social change in the context of pandemics. One of the innovative forms of archiving historical memory in the history of medicine is the Witness Seminars that was started by Professor Tillie Tansey funded by the Wellcome Trust. Such initiatives have enabled us to explore medicine and social change and in a few years if we were to similarly archive the response to COVID-19 in different countries – including patients who recovered, families who lost their loved ones, families who lost jobs and suffered other non-medical effects, doctors to worked in the frontlines and researchers who worked hard on solutions as well as those who build models with which to understand data – we would be able to build a clearer picture with such resources.

5) Is there a question you’d like to ask the readers of this interview? Could you please offer us a new idea or concept for further consideration that would deepen our collective understandings of the issues?

The question I would like to ask as a public historian – to academics as well as members of the public who are living through these uncertain times is about how cross-generational learning from experience works: Is there any learning from your family that was instigated by disasters or disease? How was this learning transmitted to you? Does the learning that formal educational institutions promote somehow undermine the learnings about disasters that come from families? In what ways can we bring these two areas of learning together to be better prepared to deal with both disasters and diseases?

– 31 March 2020

Related:

Indira Chowdhury, “Oral History and Earthquake Survivors,” Teach311.org, September 11, 2015.

Indira Chowdhury, “Oral History and the History of Scientific Practice in India: A Difficult Dialogue?” Lecture, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin, October 25, 2018.

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science(Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)